Only one month until I go home.

I am entirely conflicted about the whole affair. This has been made into my home, my hovel in Akita, Japan.

But in one month I will be gone.

What am I to do about this, I ask myself? What of the last two years of my life?

It has not been a waste. Not at all. I have evolved from a shy man resistant to talk to anyone to an outgoing person ready and willing to share his stories with everyone else. My Japanese has skyrocketed from zero to serviceable.

I have come out of my cave, and become a full person.

It is all thanks to my co-workers, my fellow teachers and ALTs, that I have evolved as much as I have.

I have gone from being too shy to talk to anyone to being able to present in front of an entire class. I have gone from having no confidence to believing my expertise in English can truly help the students understand the language in a way their JTE cannot. I have gone from being a quiet bystander to being an active participant in Japanese students' education.

In short, I have graduated from nothing to something. Students love to greet me in the city, now. "Hey, John!" is a common phrase. It makes me feel like I'm really making a difference.

In response to this, I've really tried to engage the students. Whether it's from inserting their own story into a blank comic or telling me what their day was like or whatever, I love hearing from them, in English, the highlights of their lives. It engages them in ways their memorization-focused textbooks never could.

I recently did a writing/speaking activity, using a comic from Penny Arcade. Penny Arcade was my favorite comic as a teenager, and I absolutely adored seeing my students utilize it to create their own (often very funny) stories. It made my heart sing, seeing my students create funny stories like that. This is why I signed up to be a teacher, I thought.

Soon, I'll return to America. Right as I've made a foothold here.

But it hasn't been for nothing. My experiences here have truly helped me gain teaching experience that I can use back home. I hope to God I can utilize what I've learned here in a more permanent position.

Living in Akita for two years has been an amazing experience. I wouldn't trade it for anything.

I feel so sad, leaving. Like a hole has opened in my heart. But I trust God's timing. Maybe something greater is waiting for me on the other side.

I'm really glad I got to experience the JET program.

The sun rises way too early, ramen is really as good as they say, and Don Quixote has everything

Saturday, June 15, 2019

Sunday, May 19, 2019

Value

Sometimes, it's hard to feel like you're making a difference on this job.

There are a lot of things you end up fighting against. The draconian teach-to-test-scores system that doesn't leave room for anything outside of rote drills and memorization. Other teachers not knowing what to do with ALTs at times. The kids not knowing how to react to your activities even when you are allowed to do them.

Even once you find your footing in the classroom, it's easy to ask the question; "Am I really helping?"

I ask myself this all the time. What difference would it make if I wasn't in these schools at all?

The answer never comes from within. It always comes from the students.

I was walking by the station the other day, as I so often do, living right there and all. I hear a group of kids near me whispering to each other.

"Is that sensei?"

"It is!"

"JOHN!" They call out with enthusiasm. It was a group of first years that had just arrived at my main school a month or two ago.

To tell the truth, I didn't even recognize them. There's one thousand students at that school, and I had barely gotten to know these new kids.

"Hey!" I say, putting on my biggest smile and pretending to know who they are.

"Hey, John!" One of them says. "What are you doing right now?"

"Taking a walk? Nothing, really."

"We're on break," they said.

"We haven't had your classes in a while," one of them says.

"Yeah, that's not my fault, though. I don't get to decide my schedule."

"Oh, really?"

"Yeah, if you want to have more classes with me, just ask your teacher."

Lots of "Ehhhhhhs" follow.

"I dunno. I don't feel comfortable talking to my teacher."

"Well, who's your teacher?" I ask.

They tell me.

"Yeah, I'll ask them for you."

Their faces light up.

"Really!?"

"I'm really sick of normal classes," one of them says.

This one exchange reminded me of a number of things.

One, students smile just seeing me, and are comfortable talking to me even when they don't want to talk to their real teachers. There's less of an age barrier between us, and part of an ALT's job is to be a friend or older sibling figure more than a teacher.

The students realize this. This is in direct opposition to the aformentioned draconian teaching system, where sensei is sensei and student is student. The great wall is broken when talking to the ALT. This offers students a nice break from their usual rigid school day.

Two, they actually do want to have classes with me. I always worry about my activities not lining up with the textbook, or not having any lasting impact. Regardless if they do or not, students are actually excited to have one of their teachers come to class and teach them something.

They're excited to have a lesson structured without drills or other soul-sucking memorization activities. This, alone, is enough. It opens their brains to learning in new ways.

Three, they actually want to and try to speak English with me. They see a real, living reason to want to learn the material I'm trying to teach them. They really do try and use this around me. I'm seeing living, breathing proof that English is not useless to them.

Four, because they are comfortable talking to me, I can be a liason between student and teacher. If they're ok with me talking to the other teachers, I can voice their concerns and suggestions to them, when they would otherwise be too shy to do so.

Five, it feels really nice to be recognized by someone who is glad to see you!

Of course, I think very little of this has to do with John-sensei the person, and more to do with "the ALT" that they get to interact with. But that's not the point I'm trying to make. The ALT is not useless, after all - they're a valuable asset to the students' emotional and mental wellbeing.

I think they could get by without us or our activities. But an ALT is to the Japanese school system what salt is to food. It just makes it better. We make life better for the students, in what small ways we can.

And those small ways can bloom into something larger. I've had students interested in speaking better English come to me and talk just to practice. Students who want to work overseas, or be a hotel receptionist, or work in aviation, students who will need these skills in the future or near future and see a great avenue of learning in front of them.

It feels good to help them with things like that - things that matter other than test scores.

I was lying in bed last weekend when I got a text from a student I'd met at English Cafe, an event held here in my city where native speakers play board games and talk with Japanese people. It's a good time, and many ALTs, students, and even older people come to have fun.

Anyway, this student texts me.

"Long time no see!" She says.

"You haven't been to English Cafe in a while!"

It was true. I'd skipped two or three months of it. I was feeling down and depressed. I'm leaving this summer. My time here might as well be done. How much difference can I make just playing board games and talking to people?

"Hey, long time no see! I'll be there this week for sure!" I say.

She responds with a big smiling emoji and says she'll be so glad to see me and have me there again.

I didn't know my presence was valued there at all, but here was this text, proving me wrong.

That's a recurring theme here in Japan for me. I think people don't notice things, don't appreciate things, don't remember things. I guess it might be because people don't display emotions as clearly here, but I'm always proven wrong on an astronomical level.

Students reference a funny moment from a pronunciation game we played a year ago like it's an in-joke we have going, students and other teachers comment on a change in wardrobe while referencing what you used to dress like, students give you a thank-you letter for that chocolate you gave them months and months ago out of the blue.

We are noticed, appreciated, and remembered, even if people don't always outright show us or tell us about it.

As an ALT, I may not make much of a difference in a student's test scores. But as an agent of cultural exchange, a learning experience, a friend, or just an ear willing to listen, I think an ALT can be an invaluable asset to any school or community.

I once took a selfie with the lady who runs a coffee shop near my apartment. An innocuous gesture I thought nothing of. Then the other ladies at my school said they saw it on Facebook. Then they started asking me for pictures, too. Then people started recognizing me out of the blue. "You're famous!" One of my co-workers joked. And now that ice cream/coffee shop lady always looks so happy to see me. It's the little things like this that really make you feel valued.

I'm reminded of of one particular line from the movie It's a Wonderful Life, where George is shown the world without him and how much worse off it would be.

Clarence: Strange, isn't it? Each man's life touches so many other lives. When he isn't around he leaves an awful hole, doesn't he?

There are a lot of things you end up fighting against. The draconian teach-to-test-scores system that doesn't leave room for anything outside of rote drills and memorization. Other teachers not knowing what to do with ALTs at times. The kids not knowing how to react to your activities even when you are allowed to do them.

|

| A "normal" class will involve lots of drills, and the handing back and handing out of seemingly endless tests and worksheets. |

Even once you find your footing in the classroom, it's easy to ask the question; "Am I really helping?"

I ask myself this all the time. What difference would it make if I wasn't in these schools at all?

The answer never comes from within. It always comes from the students.

I was walking by the station the other day, as I so often do, living right there and all. I hear a group of kids near me whispering to each other.

|

| The station might as well be my second home. It's also pretty much the center of the city, so I see people I know here all the time. |

"Is that sensei?"

"It is!"

"JOHN!" They call out with enthusiasm. It was a group of first years that had just arrived at my main school a month or two ago.

To tell the truth, I didn't even recognize them. There's one thousand students at that school, and I had barely gotten to know these new kids.

"Hey!" I say, putting on my biggest smile and pretending to know who they are.

"Hey, John!" One of them says. "What are you doing right now?"

"Taking a walk? Nothing, really."

"We're on break," they said.

"We haven't had your classes in a while," one of them says.

"Yeah, that's not my fault, though. I don't get to decide my schedule."

"Oh, really?"

"Yeah, if you want to have more classes with me, just ask your teacher."

Lots of "Ehhhhhhs" follow.

"I dunno. I don't feel comfortable talking to my teacher."

"Well, who's your teacher?" I ask.

They tell me.

"Yeah, I'll ask them for you."

Their faces light up.

"Really!?"

"I'm really sick of normal classes," one of them says.

This one exchange reminded me of a number of things.

One, students smile just seeing me, and are comfortable talking to me even when they don't want to talk to their real teachers. There's less of an age barrier between us, and part of an ALT's job is to be a friend or older sibling figure more than a teacher.

The students realize this. This is in direct opposition to the aformentioned draconian teaching system, where sensei is sensei and student is student. The great wall is broken when talking to the ALT. This offers students a nice break from their usual rigid school day.

Two, they actually do want to have classes with me. I always worry about my activities not lining up with the textbook, or not having any lasting impact. Regardless if they do or not, students are actually excited to have one of their teachers come to class and teach them something.

They're excited to have a lesson structured without drills or other soul-sucking memorization activities. This, alone, is enough. It opens their brains to learning in new ways.

Three, they actually want to and try to speak English with me. They see a real, living reason to want to learn the material I'm trying to teach them. They really do try and use this around me. I'm seeing living, breathing proof that English is not useless to them.

Four, because they are comfortable talking to me, I can be a liason between student and teacher. If they're ok with me talking to the other teachers, I can voice their concerns and suggestions to them, when they would otherwise be too shy to do so.

Five, it feels really nice to be recognized by someone who is glad to see you!

Of course, I think very little of this has to do with John-sensei the person, and more to do with "the ALT" that they get to interact with. But that's not the point I'm trying to make. The ALT is not useless, after all - they're a valuable asset to the students' emotional and mental wellbeing.

|

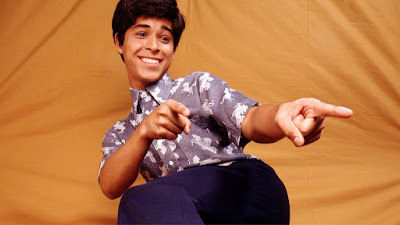

| Could being an ALT actually mean something? I think the answer is yes. |

I think they could get by without us or our activities. But an ALT is to the Japanese school system what salt is to food. It just makes it better. We make life better for the students, in what small ways we can.

And those small ways can bloom into something larger. I've had students interested in speaking better English come to me and talk just to practice. Students who want to work overseas, or be a hotel receptionist, or work in aviation, students who will need these skills in the future or near future and see a great avenue of learning in front of them.

It feels good to help them with things like that - things that matter other than test scores.

I was lying in bed last weekend when I got a text from a student I'd met at English Cafe, an event held here in my city where native speakers play board games and talk with Japanese people. It's a good time, and many ALTs, students, and even older people come to have fun.

Anyway, this student texts me.

"Long time no see!" She says.

"You haven't been to English Cafe in a while!"

It was true. I'd skipped two or three months of it. I was feeling down and depressed. I'm leaving this summer. My time here might as well be done. How much difference can I make just playing board games and talking to people?

"Hey, long time no see! I'll be there this week for sure!" I say.

She responds with a big smiling emoji and says she'll be so glad to see me and have me there again.

I didn't know my presence was valued there at all, but here was this text, proving me wrong.

That's a recurring theme here in Japan for me. I think people don't notice things, don't appreciate things, don't remember things. I guess it might be because people don't display emotions as clearly here, but I'm always proven wrong on an astronomical level.

Students reference a funny moment from a pronunciation game we played a year ago like it's an in-joke we have going, students and other teachers comment on a change in wardrobe while referencing what you used to dress like, students give you a thank-you letter for that chocolate you gave them months and months ago out of the blue.

We are noticed, appreciated, and remembered, even if people don't always outright show us or tell us about it.

As an ALT, I may not make much of a difference in a student's test scores. But as an agent of cultural exchange, a learning experience, a friend, or just an ear willing to listen, I think an ALT can be an invaluable asset to any school or community.

I once took a selfie with the lady who runs a coffee shop near my apartment. An innocuous gesture I thought nothing of. Then the other ladies at my school said they saw it on Facebook. Then they started asking me for pictures, too. Then people started recognizing me out of the blue. "You're famous!" One of my co-workers joked. And now that ice cream/coffee shop lady always looks so happy to see me. It's the little things like this that really make you feel valued.

I'm reminded of of one particular line from the movie It's a Wonderful Life, where George is shown the world without him and how much worse off it would be.

Clarence: Strange, isn't it? Each man's life touches so many other lives. When he isn't around he leaves an awful hole, doesn't he?

It'll be a bit sad to leave, I think. But the real star isn't me, it's the role. I hope whoever comes to fill my shoes will find as much hidden value in it as I did.

Wednesday, March 13, 2019

Banter

The biggest benefit of learning Japanese hasn't been gaining the ability to read street signs, talk to my co-workers, or re-order things on the phone.

It's been being able to understand the things my students say.

Here are some short examples of some of my favorite conversations.

Context: Doing an activity where they had to list things starting with a certain letter. For example, an item you put in the fridge that starts with K.

Student A, very proud of himself: "KITCHEN CLEANER!"

Student B: "Ah, yeah!"

Student B, immediately after: "Wait, what kind of weirdo puts kitchen cleaner in the fridge?"

Student A: "Oh, good point."

Context: Doing an interview activity.

Student A (in English): When is your brother's birthday?

*From here it was in Japanese*

Student B: "Uh... I don't know."

Student A: "You don't know your brother's birthday!? What kind of brother are you?"

Student B: "I really don't know, though."

Student B, suddenly in English: "I don't like my brother, so I don't know."

Student B, again in English: "Wait, my brother is dead!"

Student A, in English: "He's dead? He's DEAD!? OH MY GOD!!"

Student B, in Japanese again: "Ah, what a sad story! I can't believe my brother is dead!"

His brother was not, in fact, dead.

Context: Two friends goofing off when they were supposed to do an activity.

Student A: "I can't talk to girls."

Student B: "They wouldn't notice you anyway."

Student A: "Whoa. That was harsh. You - you're like the grim reaper. Your heart is totally black."

Context: Trying to think of ice cream flavors that start with B.

Student A: "John, is banana ok?"

Me: "I've... never seen banana flavored ice cream before. Have you?"

Student A: "No."

Student B: "Me neither."

Me: "Do you think it might exist, though?"

Student A: "I don't know."

Student B: "Probably."

Me: "Yeah, probably somewhere."

Student A: "Banana it is!"

Student B: "I absolutely need to find banana ice cream now."

Context: Students commenting on my haircut, which was basically a buzz cut at the time.

Student A, in English: "You cutting hair."

Me: "Yes, I got a hair cut."

Student A: "It looks good."

Student B: "You look like Frieza from Dragon Ball."

Thanks.

Context: Me arranging the little chicken plush things the ALT before me made before class started.

Student A: "I love those."

Me: "Me too. I think the ALT before me made them."

Student A: "Oh yeah, I knew him."

Student B: "It's like a little chicken army."

Student A, picking one up: "This is my brother."

Me: "Your brother?"

Student A: "Yes. He's my precious little brother. I won't ever let anything happen to him."

Ok then.

It's those little conversations that really add spice to your day.

As an aside, I walked into the English room the other day to find those same little chicken things arranged in front of the tape recorder, as if performing some sort of ritual.

Despite breaking the language barrier, I don't always understand my students... but I sure do love them.

It's been being able to understand the things my students say.

Here are some short examples of some of my favorite conversations.

Context: Doing an activity where they had to list things starting with a certain letter. For example, an item you put in the fridge that starts with K.

Student A, very proud of himself: "KITCHEN CLEANER!"

Student B: "Ah, yeah!"

Student B, immediately after: "Wait, what kind of weirdo puts kitchen cleaner in the fridge?"

Student A: "Oh, good point."

Context: Doing an interview activity.

Student A (in English): When is your brother's birthday?

*From here it was in Japanese*

Student B: "Uh... I don't know."

Student A: "You don't know your brother's birthday!? What kind of brother are you?"

Student B: "I really don't know, though."

Student B, suddenly in English: "I don't like my brother, so I don't know."

Student B, again in English: "Wait, my brother is dead!"

Student A, in English: "He's dead? He's DEAD!? OH MY GOD!!"

Student B, in Japanese again: "Ah, what a sad story! I can't believe my brother is dead!"

His brother was not, in fact, dead.

Context: Two friends goofing off when they were supposed to do an activity.

Student A: "I can't talk to girls."

Student B: "They wouldn't notice you anyway."

Student A: "Whoa. That was harsh. You - you're like the grim reaper. Your heart is totally black."

Context: Trying to think of ice cream flavors that start with B.

Student A: "John, is banana ok?"

Me: "I've... never seen banana flavored ice cream before. Have you?"

Student A: "No."

Student B: "Me neither."

Me: "Do you think it might exist, though?"

Student A: "I don't know."

Student B: "Probably."

Me: "Yeah, probably somewhere."

Student A: "Banana it is!"

Student B: "I absolutely need to find banana ice cream now."

Context: Students commenting on my haircut, which was basically a buzz cut at the time.

Student A, in English: "You cutting hair."

Me: "Yes, I got a hair cut."

Student A: "It looks good."

Student B: "You look like Frieza from Dragon Ball."

Thanks.

Context: Me arranging the little chicken plush things the ALT before me made before class started.

Student A: "I love those."

Me: "Me too. I think the ALT before me made them."

Student A: "Oh yeah, I knew him."

Student B: "It's like a little chicken army."

Student A, picking one up: "This is my brother."

Me: "Your brother?"

Student A: "Yes. He's my precious little brother. I won't ever let anything happen to him."

Ok then.

It's those little conversations that really add spice to your day.

As an aside, I walked into the English room the other day to find those same little chicken things arranged in front of the tape recorder, as if performing some sort of ritual.

Despite breaking the language barrier, I don't always understand my students... but I sure do love them.

Monday, March 4, 2019

Spirit

In Japan, non-conformity is a sin.

It's your duty to be the best you can be, at any given time. To follow the rules to the letter. To shoot for the stars, to go above and beyond.

Failure to meet these standards gets you the glare of disapproval, the crack of the metaphorical whip, the ostraciziation of those in authority.

It's not just Japan. I noticed this in America, too, although it manifested differently. There is a large amount of pressure to do well and make a name for yourself, to pull yourself up by your bootstraps, to follow the Baby Boomer's legacy of pursuing the American Dream.

The Japanese Dream is startlingly similar, although the key difference is that there's less room for those within it to become disillusioned with it, question it, or come to terms with not being able to reach it. In America, the fading dream has been a narrative slowly gaining steam, leaving a little leeway for people to accept finding alternative paths in life. In Japan, those alternative paths retain a certain stigma.

Of course, I'm generalizing. Of course, I'm being slightly reductive. But this is my personal impression of the larger picture of Japanese society.

It makes me mad.

Of course, it's good to shoot for the stars. But not everyone is capable of reaching every star in the sky. Sometimes people need to take another route to get there. Sometimes people have their own special stars that nobody else can get to, and that nobody else even notices are there.

I will use myself as a personal example. I am horrendous at math of any sort. I have never been able to work with numbers well. As such, I was never good at math or science class. Any job in programming, medicine, or accounting is likely closed off to me forever because of this.

Does this make me a lesser person than those who can do these things?

No, it doesn't.

At the risk of sounding like I'm patting myself on the back, I'm pretty good with words, I have a decent sense of humor (I think), and I'm good at public speaking. Can I ever be a rocket scientist with those skills? No, but I can be other things that the world needs. I couldn't write this blog if I didn't have these skills.

Not that the world needs my blog, but I digress.

Spending time in Japan, where saving face and pretending like you are good at everything is extremely common, has only made me realize how important it is to recognize people's individual strengths and talents, and not to view what they can't do as a form of personal weakness or failure.

Working as a teacher, it's your job to nurture each student's strengths and help them find their path in life. In a society so focused on test scores, however, this is a bit more difficult to do.

I work at an art school once a week, which I love dearly. This school is a bit of a black sheep, because A) it's a liberal arts school in Japan, B) the number of students is staggeringly low, and C) it exists specifically to cater to student's individual talents, with curriculums in architecture, metalworking, painting, etc.

I absolutely love that this school exists, and each student there seems very content with themselves, very happy with their choice to go there. But it, unfortunately, has a bit of a stigma to it. When I tell others I teach at this school, I hear things like "I hear the kids there are a bit odd," or "I wonder about an art school."

It really is a shame.

My first impression of the JET community I got while at a block meeting in another city, watching my senpai JETs give enthusiastic and in-depth presentations with gusto and charisma, was that these are the kinds of people who will go on to do TED talks. I was just a guy by comparison. Did I even belong here?

For a long time on JET, especially in my relatively close ALT community, I felt like I was a man living among giants.

At some point, I realized that that sort of thinking was making me miserable. I'm never going to be like them, because I'm not them. I have my own aspirations and hobbies and talents. The comparisons I was drawing between myself that nebulous blob of "the others" was an imaginary line I had created, a perception that those same others likely didn't even share.

You heard it a lot, at least growing up when I did in the U.S., that everyone is unique. You hear a lot from people my age that that narrative doesn't hold up in the real world, that we're not as unique as we were told we were, that our individuality doesn't matter as much as we were led to believe.

Living in Japan, the land of conformity and social zeitgeists, has only reinvigorated the notion of personal strengths for me. Watching the faces on my students light up as I tell them what they did right instead of reprimanding them for failing to meet expectations is one of the best feelings in the world.

I had a teacher in high school once comment on how the absence of one student entirely changed the atmosphere of the classroom. She was right - that one kid DID affect the atmosphere in a very strong way. That's the indescribable human spirit, I think, the underlying soul that can't be quantified. And that's what we can give to the world, that unquantifiable gift and power that only we have.

It's good to fit in and contribute to society. But it's equally as important to recognize that the way each person contributes to it is their own. Whether it's understanding rocket science or simply making other people laugh, each person's spirit is valuable in its own way, I think.

It's your duty to be the best you can be, at any given time. To follow the rules to the letter. To shoot for the stars, to go above and beyond.

Failure to meet these standards gets you the glare of disapproval, the crack of the metaphorical whip, the ostraciziation of those in authority.

It's not just Japan. I noticed this in America, too, although it manifested differently. There is a large amount of pressure to do well and make a name for yourself, to pull yourself up by your bootstraps, to follow the Baby Boomer's legacy of pursuing the American Dream.

|

| A husband/wife, a house, a dog, kids, and a place to grill food and invite guests over. I guess you're "supposed" to have these things, although it's a fading narrative these days. |

Of course, I'm generalizing. Of course, I'm being slightly reductive. But this is my personal impression of the larger picture of Japanese society.

It makes me mad.

Of course, it's good to shoot for the stars. But not everyone is capable of reaching every star in the sky. Sometimes people need to take another route to get there. Sometimes people have their own special stars that nobody else can get to, and that nobody else even notices are there.

I will use myself as a personal example. I am horrendous at math of any sort. I have never been able to work with numbers well. As such, I was never good at math or science class. Any job in programming, medicine, or accounting is likely closed off to me forever because of this.

Does this make me a lesser person than those who can do these things?

No, it doesn't.

At the risk of sounding like I'm patting myself on the back, I'm pretty good with words, I have a decent sense of humor (I think), and I'm good at public speaking. Can I ever be a rocket scientist with those skills? No, but I can be other things that the world needs. I couldn't write this blog if I didn't have these skills.

Not that the world needs my blog, but I digress.

Spending time in Japan, where saving face and pretending like you are good at everything is extremely common, has only made me realize how important it is to recognize people's individual strengths and talents, and not to view what they can't do as a form of personal weakness or failure.

Working as a teacher, it's your job to nurture each student's strengths and help them find their path in life. In a society so focused on test scores, however, this is a bit more difficult to do.

I work at an art school once a week, which I love dearly. This school is a bit of a black sheep, because A) it's a liberal arts school in Japan, B) the number of students is staggeringly low, and C) it exists specifically to cater to student's individual talents, with curriculums in architecture, metalworking, painting, etc.

I absolutely love that this school exists, and each student there seems very content with themselves, very happy with their choice to go there. But it, unfortunately, has a bit of a stigma to it. When I tell others I teach at this school, I hear things like "I hear the kids there are a bit odd," or "I wonder about an art school."

It really is a shame.

My first impression of the JET community I got while at a block meeting in another city, watching my senpai JETs give enthusiastic and in-depth presentations with gusto and charisma, was that these are the kinds of people who will go on to do TED talks. I was just a guy by comparison. Did I even belong here?

|

| Other JETs, as seen through John-o-vision in the year 2017 |

At some point, I realized that that sort of thinking was making me miserable. I'm never going to be like them, because I'm not them. I have my own aspirations and hobbies and talents. The comparisons I was drawing between myself that nebulous blob of "the others" was an imaginary line I had created, a perception that those same others likely didn't even share.

You heard it a lot, at least growing up when I did in the U.S., that everyone is unique. You hear a lot from people my age that that narrative doesn't hold up in the real world, that we're not as unique as we were told we were, that our individuality doesn't matter as much as we were led to believe.

Living in Japan, the land of conformity and social zeitgeists, has only reinvigorated the notion of personal strengths for me. Watching the faces on my students light up as I tell them what they did right instead of reprimanding them for failing to meet expectations is one of the best feelings in the world.

I had a teacher in high school once comment on how the absence of one student entirely changed the atmosphere of the classroom. She was right - that one kid DID affect the atmosphere in a very strong way. That's the indescribable human spirit, I think, the underlying soul that can't be quantified. And that's what we can give to the world, that unquantifiable gift and power that only we have.

It's good to fit in and contribute to society. But it's equally as important to recognize that the way each person contributes to it is their own. Whether it's understanding rocket science or simply making other people laugh, each person's spirit is valuable in its own way, I think.

Thursday, February 21, 2019

Lingo

I have spent my entire life obsessed with words.

When I was a kid, I used to get very frustrated when I couldn't convey my thoughts properly, or when people didn't understand me. Miscommunication, or simply lacking the ability to put my thoughts into words, was the worst feeling in the world.

So I decided to spend my life honing my wordsmithing. Never again would I be lacking for prose or precision. People would always know exactly what I wanted to say.

I think I did an ok job. I got a B.A. in English, I went to grad school for English Education, I worked as a journalist for a while, and I was always, always writing in my spare time. I can put my thoughts into words with relative ease now. Finally free of that pesky nagging feeling of not being able to properly express myself!

Right?

Well... no.

Moving to Japan put that all in a wet blanket and tossed it out the window.

I spoke very little Japanese when I came here. Over a year and a half, it's gotten better, but is still very broken. Communication has been one of, if not the hardest, barrier to overcome in moving here, made exponentially more frustrating because I spent my entire life working to avoid this problem.

Communication problems have phases.

Phase 1 is what I like to call the WTF Phase. In this phase, every word is a freight train coming at you at full speed, which means a full sentence will leave you floored in seconds. You're essentially made into a mute clown, because all you have is your gestures and your gibberish that nobody around you can understand. Nothing makes any sense, and you have to dance to get directions.

Oh, and if you're in Japan, you can't read, either. Every sign might as well be the glyphs on the Dead Sea Scrolls.

It feels a lot like being on a tiny boat in a vast ocean in the middle of a hurricane. You struggle and struggle just to stay above water, let alone on staying on your boat, let alone focusing on getting to your destination.

It sucks.

Phase 2 is what I like to call the Drunken Haze Phase. In this phase, you can understand general concepts when people talk to you - sometimes - and the language doesn't sound like a garbled radio anymore. You yourself can utter basic subjects and verbs, so you can neanderthal yourself through everyday life using phrases like "That. Need." or "Go here. How?" Maybe you can read a little.

Things kind of make sense, but also not really. I've never done drugs, but I imagine that it's a lot like being high, or going on an acid trip. The world is kind of comprehensible, but also very twisted, and your window of observation is definitely not accurate. You can stumble your way through life - like a half-drunken mess brute forcing your way through everything, maybe - but you can still sort of do it!

You're still on your tiny boat in the middle of the ocean, but the hurricane isn't there harassing you anymore.

Phase 3 is what I like to call the Fez Phase. If you've ever seen That 70's Show, Fez - a nickname that's short for Foreign Exchange Student - is the token comedy relief character. He's allowed to say outrageous things and be oblivious to cultural conventions and break social rules and generally just be a goofball without anyone thinking about it too much.

This is you when you can speak and read well enough.

Your grammar or vocabulary is still a bit lacking, you have an accent, you can read a decent amount. You're functioning! But you're still not a part of the system. Since you can talk, though, people might not be afraid to approach you anymore. You get to teach people about the way you do things in your country, you get to break rules and societal expectations and be the "fun guy" to be around, and you can finally be a part of society, albeit in a weird and off-beat way.

You're on the boat, and now you have a paddle, too.

I think there is a Phase 4, which I would call the Zeus Phase, because you might as well be a God if you get there. This means perfect speaking and comprehension skills, being able to read everything, and maybe even losing your accent. I know people who have done this, but they are superhuman, and quite frankly I think they are just a bunch of stupid overachievers. Nerds.

I'm not jealous, ok!?

Those people are cruisin', though. Their boat has a motor on it.

While going through these phases, I realized that communication is a lot more than words. Even if you explain yourself to someone with absolutely perfect clarity, they still might not see where you're coming from, because their customs and ideology and whatever else might not gel with what you're saying. And even if you can't say a word, sometimes you can get your point across anyway.

Conveying ideas to other people is a lot more than just stringing words together. Communication is a complicated beast, made up of many different layers. It helps to have the deeper layers mastered, but the outer ones matter just as much. Smiling at people to let them know you're not uncomfortable means a lot, for example, and you can always tell a lot about what people are feeling from looking at their eyes, which I think show more genuine emotion than any words can or do.

Personally, I feel like I almost lost sight of that in my pursuit of perfect prose.

I'm still paddling my boat. I don't think I'll ever get a motor on mine. But that's ok. I like being the goofball anyway.

The few times I have returned home, suddenly regaining the ability to speak coherent sentences has been startling, like evolving from a monkey to a man in the span of a 20 hour flight.

Never underestimate how good it feels to be able to communicate. I love Japan, but that's one thing I'm looking forward to when I go home again.

When I was a kid, I used to get very frustrated when I couldn't convey my thoughts properly, or when people didn't understand me. Miscommunication, or simply lacking the ability to put my thoughts into words, was the worst feeling in the world.

So I decided to spend my life honing my wordsmithing. Never again would I be lacking for prose or precision. People would always know exactly what I wanted to say.

|

| I wanted to be like Shakespeare, man. Master wordsmith! |

Right?

Well... no.

Moving to Japan put that all in a wet blanket and tossed it out the window.

|

| A still shot of my language skills, shortly before their death |

Communication problems have phases.

Phase 1 is what I like to call the WTF Phase. In this phase, every word is a freight train coming at you at full speed, which means a full sentence will leave you floored in seconds. You're essentially made into a mute clown, because all you have is your gestures and your gibberish that nobody around you can understand. Nothing makes any sense, and you have to dance to get directions.

Oh, and if you're in Japan, you can't read, either. Every sign might as well be the glyphs on the Dead Sea Scrolls.

It feels a lot like being on a tiny boat in a vast ocean in the middle of a hurricane. You struggle and struggle just to stay above water, let alone on staying on your boat, let alone focusing on getting to your destination.

It sucks.

Phase 2 is what I like to call the Drunken Haze Phase. In this phase, you can understand general concepts when people talk to you - sometimes - and the language doesn't sound like a garbled radio anymore. You yourself can utter basic subjects and verbs, so you can neanderthal yourself through everyday life using phrases like "That. Need." or "Go here. How?" Maybe you can read a little.

Things kind of make sense, but also not really. I've never done drugs, but I imagine that it's a lot like being high, or going on an acid trip. The world is kind of comprehensible, but also very twisted, and your window of observation is definitely not accurate. You can stumble your way through life - like a half-drunken mess brute forcing your way through everything, maybe - but you can still sort of do it!

You're still on your tiny boat in the middle of the ocean, but the hurricane isn't there harassing you anymore.

Phase 3 is what I like to call the Fez Phase. If you've ever seen That 70's Show, Fez - a nickname that's short for Foreign Exchange Student - is the token comedy relief character. He's allowed to say outrageous things and be oblivious to cultural conventions and break social rules and generally just be a goofball without anyone thinking about it too much.

This is you when you can speak and read well enough.

Your grammar or vocabulary is still a bit lacking, you have an accent, you can read a decent amount. You're functioning! But you're still not a part of the system. Since you can talk, though, people might not be afraid to approach you anymore. You get to teach people about the way you do things in your country, you get to break rules and societal expectations and be the "fun guy" to be around, and you can finally be a part of society, albeit in a weird and off-beat way.

You're on the boat, and now you have a paddle, too.

I think there is a Phase 4, which I would call the Zeus Phase, because you might as well be a God if you get there. This means perfect speaking and comprehension skills, being able to read everything, and maybe even losing your accent. I know people who have done this, but they are superhuman, and quite frankly I think they are just a bunch of stupid overachievers. Nerds.

I'm not jealous, ok!?

Those people are cruisin', though. Their boat has a motor on it.

While going through these phases, I realized that communication is a lot more than words. Even if you explain yourself to someone with absolutely perfect clarity, they still might not see where you're coming from, because their customs and ideology and whatever else might not gel with what you're saying. And even if you can't say a word, sometimes you can get your point across anyway.

Conveying ideas to other people is a lot more than just stringing words together. Communication is a complicated beast, made up of many different layers. It helps to have the deeper layers mastered, but the outer ones matter just as much. Smiling at people to let them know you're not uncomfortable means a lot, for example, and you can always tell a lot about what people are feeling from looking at their eyes, which I think show more genuine emotion than any words can or do.

Personally, I feel like I almost lost sight of that in my pursuit of perfect prose.

I'm still paddling my boat. I don't think I'll ever get a motor on mine. But that's ok. I like being the goofball anyway.

The few times I have returned home, suddenly regaining the ability to speak coherent sentences has been startling, like evolving from a monkey to a man in the span of a 20 hour flight.

Never underestimate how good it feels to be able to communicate. I love Japan, but that's one thing I'm looking forward to when I go home again.

Saturday, February 9, 2019

Other

I'm going to talk about a very uncomfortable topic, which is racism and xenophobia in Japan.

It exists. It's extremely prevalent. However, most people who exhibit this behavior are entirely unaware of what they are doing. It's the product of an extremely homogeneous, isolated society, where foreigners, despite their recently increasing numbers, are still the VAST minority.

We aren't just black sheep. We're like a God damn dinosaur in the middle of the herd.

Japan is a highly educated, first world country. It knows what racism is. People know it's bad. But because actual interaction with the outside world is so few and far between, people know of it, as something they've learned of in textbooks and seen on television, but have trouble conceptualizing it as something that exists in the real world.

As such, when met with a foreigner, you'll find situations like...

-Long stares

-Visible desire to avoid you

-Awkward smiles

-Refusal to acknowledge your Japanese (often accompanied by "I don't speak English" or scattered English phrases)

-Conversely, the compliment "Nihongo jouzu" ("your Japanese is very good") after saying something super simple, like "how much is this" or "where is the bus stop"

And such.

Some of my favorite personal examples have been people telling me my nose is huge, children pointing at me and screaming "foreigner!!!", other teachers openly talking about how they find foreigners scary because they don't know how to talk to them (thinking I couldn't understand them), my students asking me if my eyes are real and if I see differently from normal people, and, the biggest of all, sitting in on a world history class about the physical and cultural differences between Japanese people and the rest of the world.

That lesson was something else. The teacher mentioned how black people love to eat watermelon and dance before singling me out as the "white guy" example, asking me to stand up, pointing out my nose, eyes, and hair as different, all before saying Americans tend to be louder and care about their own opinions a lot.

In the west, we call these things microaggressions. They aren't hostile in nature - often quite the opposite - but they are offensive because you are being compartmentalized, dehumanized, and put in a very different space from "normal" human beings.

It's not a good feeling, being put in a different zone like that.

Of course, not everyone is like this. If I were to make a generalization like that, I'd be doing exactly what I'm complaining about. There are loads of nice and understanding and wonderful people without a hint of this behavior. But it would be disingenuous to say that it wasn't very prolific here.

So what can we do to combat this?

The answer is - not much.

The best we can do is learn Japanese, get involved with the community, and make friends. You can't tell someone they're being slightly xenophobic - you need to show them you're a normal human being. Then they hopefully realize the error of their ways, in retrospect.

Since I'm a white guy, I normally don't experience this stuff in America. I know a lot of people would probably say something along the lines of "cry me a river" for the soft-racism I experience here as opposed to the real, dangerous kind back home.

I suppose they wouldn't be off base in saying something like that. One of the only ways to experience what it actually feels like to be a minority is to become one.

And, in many ways, it's been enlightening. I would actually go so far as to say that all non-minorities should experience it in their lives at some point. It drives home how important it is to really see other people, their hearts and not their face, to respect them and talk to them, not at them.

It's been interesting. I really hope that, as Japan continues to globalize itself, that the problem can diminish over time.

|

| A "skin whitening" booth near my house, created to take your photo and make you look more like a white person. |

It exists. It's extremely prevalent. However, most people who exhibit this behavior are entirely unaware of what they are doing. It's the product of an extremely homogeneous, isolated society, where foreigners, despite their recently increasing numbers, are still the VAST minority.

We aren't just black sheep. We're like a God damn dinosaur in the middle of the herd.

|

As such, when met with a foreigner, you'll find situations like...

-Long stares

-Visible desire to avoid you

-Awkward smiles

-Refusal to acknowledge your Japanese (often accompanied by "I don't speak English" or scattered English phrases)

-Conversely, the compliment "Nihongo jouzu" ("your Japanese is very good") after saying something super simple, like "how much is this" or "where is the bus stop"

And such.

Some of my favorite personal examples have been people telling me my nose is huge, children pointing at me and screaming "foreigner!!!", other teachers openly talking about how they find foreigners scary because they don't know how to talk to them (thinking I couldn't understand them), my students asking me if my eyes are real and if I see differently from normal people, and, the biggest of all, sitting in on a world history class about the physical and cultural differences between Japanese people and the rest of the world.

That lesson was something else. The teacher mentioned how black people love to eat watermelon and dance before singling me out as the "white guy" example, asking me to stand up, pointing out my nose, eyes, and hair as different, all before saying Americans tend to be louder and care about their own opinions a lot.

In the west, we call these things microaggressions. They aren't hostile in nature - often quite the opposite - but they are offensive because you are being compartmentalized, dehumanized, and put in a very different space from "normal" human beings.

|

| Gaijin is a slang term for foreigner. It can be considered offensive. |

It's not a good feeling, being put in a different zone like that.

Of course, not everyone is like this. If I were to make a generalization like that, I'd be doing exactly what I'm complaining about. There are loads of nice and understanding and wonderful people without a hint of this behavior. But it would be disingenuous to say that it wasn't very prolific here.

So what can we do to combat this?

The answer is - not much.

The best we can do is learn Japanese, get involved with the community, and make friends. You can't tell someone they're being slightly xenophobic - you need to show them you're a normal human being. Then they hopefully realize the error of their ways, in retrospect.

Since I'm a white guy, I normally don't experience this stuff in America. I know a lot of people would probably say something along the lines of "cry me a river" for the soft-racism I experience here as opposed to the real, dangerous kind back home.

I suppose they wouldn't be off base in saying something like that. One of the only ways to experience what it actually feels like to be a minority is to become one.

And, in many ways, it's been enlightening. I would actually go so far as to say that all non-minorities should experience it in their lives at some point. It drives home how important it is to really see other people, their hearts and not their face, to respect them and talk to them, not at them.

It's been interesting. I really hope that, as Japan continues to globalize itself, that the problem can diminish over time.

Monday, February 4, 2019

Prism

An article about China in a blog about life in Japan. What gives?

Well, I've been exposed to all sorts of cultures here, and Chinese is one of them. Ironically, most of the people I've met with Chinese roots here speak English. Go figure.

JET is useful for more than one form of cultural exchange, it seems.

Food motivates me to do a lot of things.

I'm probably one of the least qualified people to talk about the Lunar New Year. I have never celebrated it before. The extent of my knowledge is in its food, and from what I have read and heard about secondhand. All I can do is talk about it from the window of an outsider.

But that has its own value, right?

This year is the year of the pig. Of all the twelve Chinese zodiac animals, I always felt bad for those born in the year of the pig or the rat. Especially when you have tigers and dragons as an alternative.

Supposedly, though, people born in the year of the pig are blessed with great fortune and prosperity, destined to be cared for for the rest of their lives.

I guess that doesn't sound so bad.

I love how each Chinese sign can be further divided into its own element. There's Water, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Wood. This is the year of the Earth Pig. I was born in the year of the Earth Dragon, apparently. That sounds so cool. It's like something out of Harry Potter, or Naruto, or Power Rangers, or any other kid's series where they get powers based on their individual personalities.

Maybe that's why some people are so drawn to this stuff. It has a fantastical twinge to it, something magical that makes you feel special by fitting into a particular, specialized category.

I've always found zodiacs and horoscopes tangentially interesting, on a surface level. I think most of it is nonsense, personally. I'm sure as hell not gonna let a cluster of stars determine my day or week or year or life, but it is fun to see how some people try to draw meaning from these cosmic things.

It's even more interesting when you compare it between cultures.

Under the western zodiac signs, someone born today would be an Aquarius, the sign of the future.

Someone born as an Aquarius is said to be:

-Unique

-Popular

-Ambitious

As well as strongly motivated by things that they want, ways to fulfill their ambition.

Meanwhile, someone born in the year of the pig is said to be:

-Materialistic

-Enthusiastic

-Realistic

As well as value positions of leadership, and be a person of action rather than words.

Those sound pretty similar, don't they? They can certainly co-exist. But still, they each have their own vibe to them, their own perspective. It's the same concept being viewed through a different window, each window having its own tint to it.

Zodiac signs may be a bunch of fluff, but as a form of cultural comparison, they're pretty neat, I think.

Seeing the different ways people interpret concepts like this is incredibly interesting. Celebrating a new year is a singular idea, but like all things on Earth, passes through a prism before being interpreted into something of cultural significance.

The western New Year I grew up with, the New England celebration of chip dip and miniature hot dogs and the ball dropping, is only one color of that rainbow, with dumplings and egg rolls and lantern festivals being another.

|

| I would love to see a lantern festival in person someday. |

Like an instagram photo with different filters, for a modern analogy.

One of the better parts of life is getting to see those different rays of light, to go from place to place and take in all of the colors coming from that prism.

And to eat the food under each ray of light.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)